Decline of local government town planning powers - a timeline

- David

- Feb 9, 2024

- 7 min read

The last post in this blog discussed state government led changes to introduce more medium density housing across the state.

While arguably, many of these changes make sense from an environmental, social, economic and town planning perspective, they represent the continuation of a long term trend that has been occurring for 50 years or more, where the ability of local Councils to plan for and control development in their areas has been greatly diminished.

As a substitute for the above, many elements of town planning have been privatised and power has also become more centralised at a state government level, notably within what is now known as the Department of Planning, Housing and Infrastructure.

The decline of local government does not only relate to town planning, for example local government previously had a role in electricity supply and Sydney-based Councils had substantial influence over the former Metropolitan Water Sewerage and Drainage Board.

This timeline starts in 1945, since it is a good starting point.

At this time, basically all forms of town planning and development certification were handled by Councils under the Local Government Act 1919. Due to the lack of constitutional status of local government in Australia, local government in NSW was a creation of state government under this Act and the Minister for Local Government had certain powers under the Act. There was no formal state government planning body at this time, however.

The Local Government Act 1919 was amended by the Local Government (Town and Country Planning) Amendment Act 1945. This Act substantially built on the existing town

planning provisions in the Local Government Act 1919. Amongst changes introduced as part of the amendment Act, were provisions for the creation of “planning schemes” by Councils and a list of detailed planning matters that could be included in those schemes.

The Act also provided for the involvement of the Minister with Councils in preparing these schemes. These schemes came to be known as “Planning Scheme Ordinances” (PSOs). They have now mostly all been replaced by local environmental plans throughout the state. A provision for “interim development orders” (IDOs) was established whereby the provisions of a planning scheme could be suspended by the Minister to allow for a form of “interim development” to be performed on land. A legislative procedure existed in terms of the making of IDOs.

The Cumberland County Council was established under the Local Government (Town and Country Planning) Amendment Act 1945.

Cumberland County Council essentially covered the boundaries of the metropolitan area of present day Sydney. The Cumberland County Council was established to address a perceived urgent need for an organised town planning scheme in Sydney and operated as a county Council under the provisions of the Local Government Act, governed by representatives of the various local Councils within its area.

The Cumberland County Council was not elected by the people, but rather was elected by councillors of the various local governments within the county. The council consisted of 10 councillors each elected to a single constituency: No. 1 (Sydney), No. 2 (Marrickville, Canterbury), No. 3 (Randwick, Botany, Woollahra, Waverley), No. 4 (Rockdale, Hurstville, Kogarah, Sutherland), No. 5 (Strathfield Ashfield, Burwood, Leichhardt, Drummoyne, Concord), No. 6 (Auburn, Bankstown, Holroyd, Parramatta), No. 7 (Mosman, Manly, North Sydney, Warringah), No. 8 (Hunter's Hill, Hornsby, Ku-ring-gai, Lane Cove, Ryde), No. 9 (Blacktown, Penrith, Baulkham Hills, Windsor) and No. 10 (Fairfield, Camden, Liverpool, Campbelltown, and parts of Wollondilly and Wollongong).

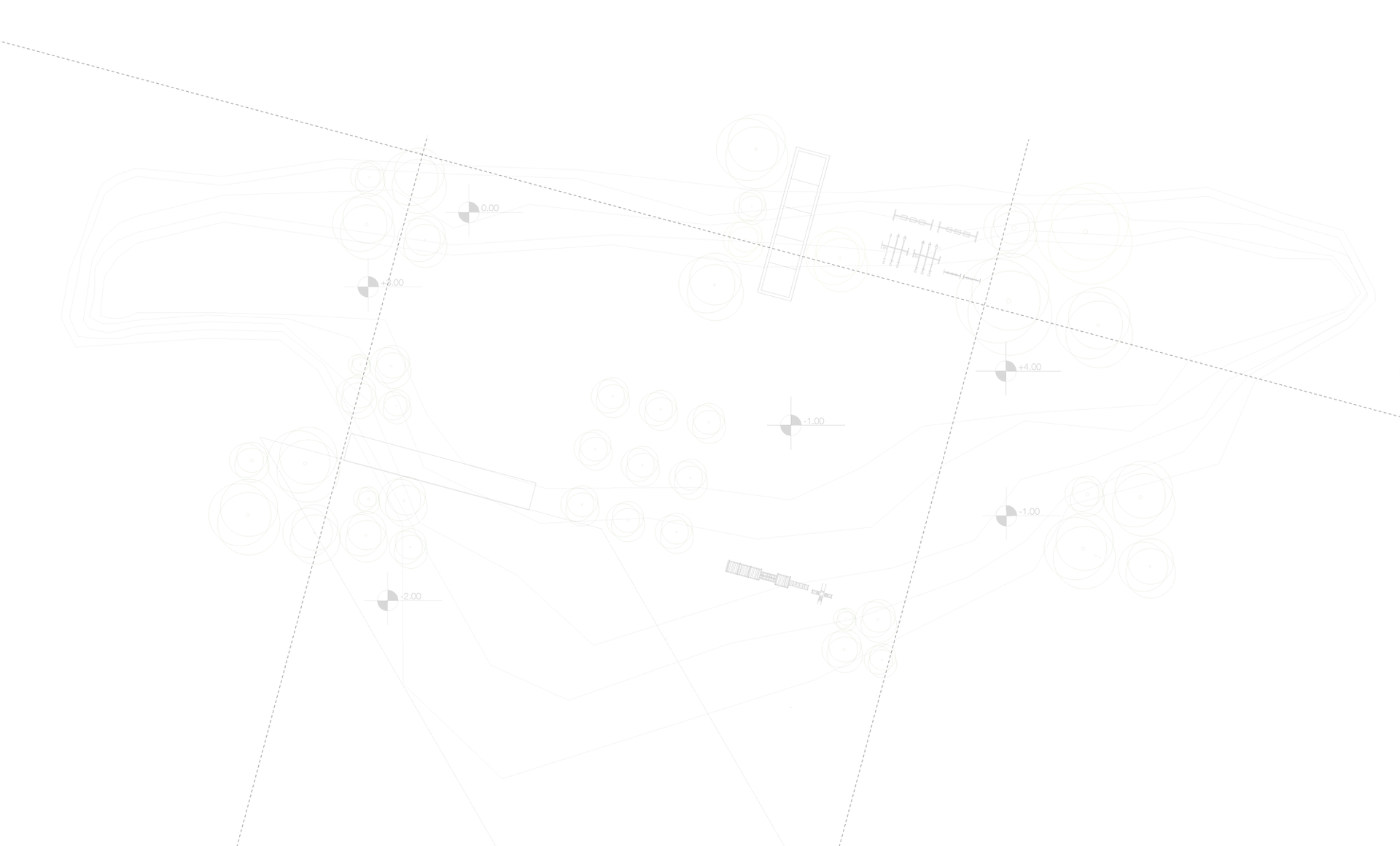

The Cumberland County Council subsequently prepared the “County of Cumberland Planning Scheme Ordinance”. This ordinance was adopted by the Council and state government in 1951. Arguably, this was the first real attempt at a government level to plan for metropolitan Sydney on a widespread scale. Key elements of the County of Cumberland Planning Scheme Ordinance were the provision of a green belt around Sydney and a radial motorway network. The plan also provided for future areas of public open space.

While town planning was predominantly the responsibility of local government and there was no state government planning body as such, the state government did play a major role through the building of housing and other infrastructure directly. The Housing Commission of NSW would have been the largest developer of housing in the post-war years, developing most of the new housing in areas such as Bankstown, Ryde, Auburn and Parramatta and redeveloping inner city areas such as Redfern/Waterloo. With state government having a higher constitutional status than local government, the Housing Commission was largely free to plan for these areas without local government interference. Similarly, the Department of Main Roads and Department of Public Works were not subject to local government control.

Arguably, it was conflict between the Cumberland County Council and state government bodies such as the Housing Commission of NSW over plans for housing that saw the Cumberland County Council abolished in 1964. Since the period between 1919 or 1945 and 1964 represents the high point of local government's role in town planning, we have seen a progressive downgrading since then (with a fast acceleration since the late 1990s), which can be described as follows:

The State Planning Authority replaced the County of Cumberland in 1963, under the State Planning Authority Act 1963. While a state government body, it's governing body included nominees of the Local Government Association and Shires Association.

The State Planning Authority was abolished in 1974 and various state bodies have succeeded it. The current Department of Planning, Housing and Infrastructure is no longer governed by a board involving local government representation.

The Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979 came into effect in 1980. This Act did not necessarily downgrade the role of local government per se. One of it's objectives is/was "to promote the sharing of the responsibility for environmental planning and assessment between the different levels of government in the State". For example, some state government bodies such as the Housing Commission of NSW were now required to lodge Development Applications with Council's, even though Councils could not refuse them without the consent of the Minister. The Act also removed provisions for IDOs, providing a much more restrictive and legal process for rezoning of lands to occur. The Act arguably provided for greater checks and balances for integrity purposes, both in development assessment and rezoning.

Private building certification was introduced in NSW in 1998. This allowed developers to have a private certifier of their choice inspect building works rather than local Councils, which essentially inspected everything except for state government works until then. Provisions for CDCs were also introduced at this time, which also eliminated the need for a DA for certain developments, bypassing Councils entirely. Initially as part of these reforms, each Council could decide what type of development would be complying development within their local area, although this choice was later removed by state government (see below).

"Part 3A" of the Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979 was introduced in 2005, which bypassed the role of local government in approving certain large developments (typically proposed by large corporations and/or the government itself). This part also largely bypassed all local planning controls. It also allowed for rezonings without following the normal process, as part of these proposals, similar to the former IDOs.

A standard LEP template was introduced in 2006, requiring Council's to follow a specific template in developing new planning controls. This reduced their level of flexibility and mandated a strict zoning approach to planning, more common in America than Europe.

SEPP (Exempt and Complying Development Codes) 2008 was introduced, which largely removed the ability of Council's to choose what type of developments could be approved by private certifiers. This policy has been extensively expanded since then to include new types eg. dual occupancies, terraces.

"Joint Regional Planning Panels" were introduced in 2009, which replaced the role of Council's in approving certain developments with panels.

In addition to the above, Council's in Sydney and Wollongong were required to introduce "Local Planning Panels" in 2018, which replaced the role of elected Councils in making Development Application decisions.

Based on the above, what are Council's still responsible for?

Some of the remaining development assessment functions that cannot/have not been privatised. eg. compliance actions where developers have not followed the correct legal process, Development Applications that cannot proceed as CDCs, building certification that is not profitable for private certifiers eg. in remote areas, for smaller developments etc.

Some limited setting of local planning controls, within an increasingly restrictive state government framework.

Being part of and coordinating an increasing number of complex, state government coordinated panels and managing more complex and numerous government directives.

Councils are still responsible for almost all roads and public parklands. Arguably, these are a more important part of town planning - as private buildings come and go, but public spaces are for the use of the entire community and can therefore be planned for the long term.

It is fair to say that local Council's do not always have the best reputation, often being criticised for slow decision making and at times corruption, which is part of the reason why state government made many of these changes. These problems are by no means unique to local government, however.

Intellectual Nassim Taleb argues that local government is actually the level of government with the highest level of "skin in the game" since it is the closest level of government to the community in which they are supposed to serve and cannot hide behind being located in a different city hundreds or thousands of kilometres away. There are probably some major matters of state and local significance that Council's are too parochial to deal with, which is why there has always been some state government involvement in planning, although there are also matters of purely local significance that are best dealt with at local level.

Local government has never been perfect and there are certainly improvements that could be made in the timing of making decisions and incentives for this, although personally I have always found local government reasonably well contactable and responsive to local needs.

Comments