Le Corbusier's "Radiant City" concept. What worked and what went wrong?

- David

- Oct 27, 2025

- 5 min read

Charles-Édouard Jeanneret known as Le Corusier was an architect, painter, urban planner and writer born in 1887.

Dedicated to providing better living conditions for the residents of crowded cities, Le Corbusier was influential in urban planning.

His ideas on urbanism were published in "Ville Radieuse" or "The Radiant City" in 1930. This was one of the most influential, and controversial, urban planning concepts of the 20th century. It was not just a design for a city but a radical manifesto for how modern society should live.

Here is a detailed description of the concept, its principles, and its legacy:

Core Philosophy: A Machine for Living

Le Corbusier saw the industrial cities of the early 20th century (like Paris) as chaotic, overcrowded, unsanitary, and inefficient—relics of a bygone era. He proposed the Radiant City as a rational, ordered, and scientific solution, a utopian machine designed to maximise health, efficiency, and social order. It was a vision intended to replace the existing urban fabric entirely.

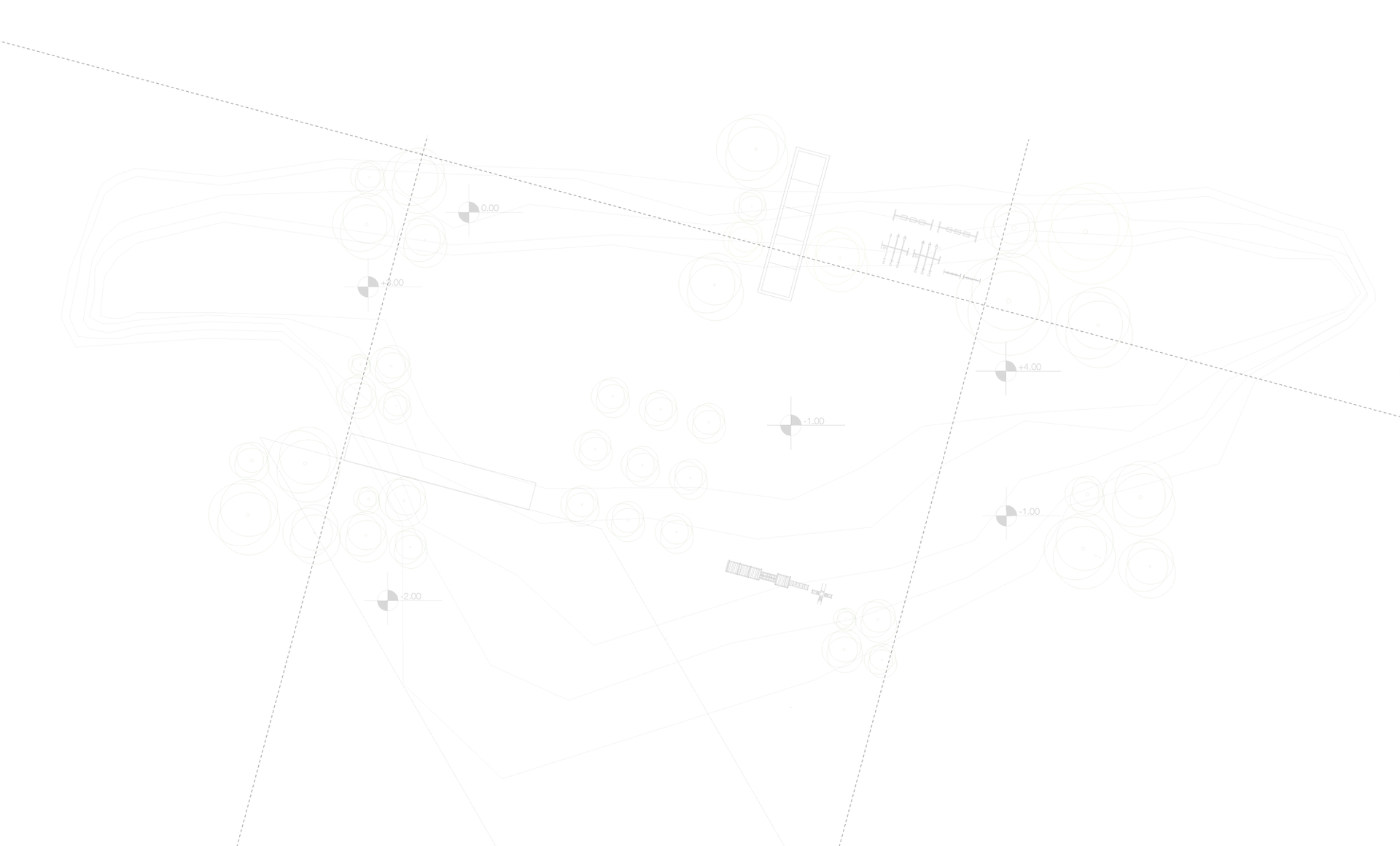

Sketch of Le Corbousier Scheme

Key Principles and Design Features

1. Strict Functional Segregation (Zoning): This is the most fundamental principle. The city was divided into separate zones for distinct functions:

Living: Vast, spacious residential blocks set in open parkland.

Working: Dedicated industrial and office sectors.

Circulation: A separate, high-capacity network for roads.

Recreation: Ample green space for leisure.

This was a direct rejection of the mixed-use, street-oriented European city.

2. The "Cartesian" Skyscraper At the heart of the residential zones were massive, identical, cruciform (cross-shaped) skyscrapers. These were not just office towers but "vertical villages" for living.

High Density: They housed a large population on a very small footprint (only 15% of the ground was built upon).

Ample Light and Air: Their cruciform shape and wide spacing ensured every apartment had sunlight and ventilation—a direct response to the dark, airless tenements of the old city.

Amenities: They contained communal services like laundries, kitchens, and gyms, freeing the individual (especially the housewife) from domestic burdens.

3. Abundance of Green Space By building vertically and concentrating the population, Le Corbusier freed up to 95% of the ground area as continuous, open green space. This "vertical garden city" was meant to provide recreation, clean air, and a healthy environment for all.

4. The Death of the Street and the Separation of Traffic Le Corbusier famously declared the traditional street to be an "obsolete and dangerous corridor." In the Radiant City, transportation was strictly segregated by speed and purpose:

Elevated "Auto-Routes": High-speed, uninterrupted roads for cars, elevated on stilts above the ground-level park.

Ground Level: Reserved exclusively for pedestrians and cyclists, who would wander safely through the parkland.

Underground: Service roads for deliveries and infrastructure.

This created a city where the car was king, but without impeding the pedestrian.

5. A "Radiant" Plan and Standardisation The entire city plan was geometric, symmetrical, and repetitive, reflecting a belief in universal order. It was to be built using modern, standardised industrial materials (steel, glass, reinforced concrete) and construction techniques, making it efficient and scalable. The name "Radiant" evoked not just sunlight but also the idea of a hopeful, enlightened future.

6. Centralised Control and Social Vision The Radiant City was not a democratic or organic proposal. It was a top-down vision that required a central planning authority to implement and maintain. Le Corbusier saw it as a tool for social engineering, creating a more efficient, healthy, and, in his view, harmonious society. It was, in essence, an authoritarian and technocratic utopia.

A Conceptual Diagram: The Radiant City Plan

Imagine a vast, flat green park. Rising from this park at regular intervals are identical, cruciform glass-and-concrete skyscrapers. Below you, the ground is open for you to walk, play, or picnic. Above you, elevated on massive concrete pillars, is a network of multi-lane highways carrying traffic at high speed between the city's functional zones (residential, business, industrial). The ground plane is for people; the upper plane is for machines.

Troieschyna Kiev Ukraine - David Carey

Legacy and Critique

The Radiant City's influence is immense, but its legacy is deeply problematic.

Influence and Adoption:

Its principles directly inspired much of the urban renewal and public housing projects in the mid-20th century, particularly in Europe and the Americas.

Elements like high-rise residential towers set in parkland, separation of uses, and car-centric planning became the standard model for modern urban development for decades.

The planned city of Chandigarh, India (designed by Le Corbusier) and the Unité d'Habitation in Marseille are direct physical manifestations of his ideas. The ideas were adopted at a wide scale in the formerly socialist countries of Eastern Europe.

Critiques:

Socially Destructive: Critics like Jane Jacobs argued that the model destroyed the very thing that makes a city vibrant: the intricate, mixed-use "street ballet" with its eyes on the street, small businesses, and social interaction. The vast, undefined green spaces between towers often became barren, unsafe, and unused. Similarly with internal corridors and lifts in high-rise buildings.

Alienating and Monotonous: The sheer scale, repetition, and lack of human-scale detail were criticised for creating a sterile, alienating, and impersonal environment.

Ignored Human Nature: The plan was based on a logical, mechanical model of human needs (sun, space, greenery) but ignored more complex social and psychological needs for community, identity, and variety.

Failed Utopia: Many housing projects based on this model (e.g., Pruitt-Igoe in the US) became synonymous with poverty, crime, and social failure, leading to their eventual demolition.

James Howard Kunstler was critical of the concept. "The ideas of (Le Corbusier) that actually found their way into practice were deeply destructive - for instance, the tower-in-a-park, which mutated into the vertical slums of the late 20th century".

Sydney Context

One of the closest real-life applications of this concept would be the Waterloo development constructed in the 1970s and 1980s by the Housing Commission of NSW. These units have many of the benefits outlined above (good access to sunlight, views, services and open space), although also many of the drawbacks (lack of direct relationship with the street, sterile and lack of passive surveillance within publicly accessible lifts and corridors, leading to crime and safety issues).

Waterloo High-Rise Public Housing Tower - Google Maps

Jane Jacobs drew a parallel between empty streets and the deserted corridors, elevators, and stairwells in high-rise public housing projects. These "blind-eyed" spaces, modelled after the upper-class standards for apartment living but lacking the amenities of access control, doormen, lift operators, engaged building management, or related supervisory functions, are ill-equipped to handle strangers, and therefore the presence of strangers becomes "an automatic menace." They are open to the public but shielded from public view, and thus "lack the checks and inhibitions exerted by eye-policed city streets," becoming flash points for destructive and malicious behaviour.

As residents feel progressively unsafe outside their apartments, they increasingly disengage from the life of the building. These troubles are not irreversible. Jacobs noted that a Brooklyn project successfully reduced vandalism and theft by opening the corridors to public view, equipping them as play spaces and narrow porches, and even letting tenants use them as picnic grounds. This article suggests that a concierge service drastically reduced many of the earlier problems with the buildings in Waterloo, although a decision was made to demolish them anyway.

(Arguably, the proposed replacement for Waterloo has as many, if not more of the drawbacks of the current scheme and as few, or less of the benefits (open space, solar access, other than perhaps slightly better street activation), although this is a separate item for discussion).

Summary

In summary, Le Corbusier's Radiant City was a powerful, seductive, and ultimately flawed vision. It successfully diagnosed the ills of the 19th-century industrial city but offered a cure that, in its pure application, proved to be worse than the disease. It remains a pivotal concept for understanding the ambitions and failures of 20th-century modernist urban planning.

Comments